With a name like Tempest Storm, you expect fireworks—and she delivered. Fiery red hair, a stare that could stop a room, and a career that ran for more than sixty years turned a small-town runaway into the queen of an art form.

She began as Annie Blanche Banks, born on Leap Day 1928 in Eastman, Georgia, where poverty and abuse were part of the landscape. At fourteen she ran, married a Marine to free herself legally, and saw it annulled a day later. By fifteen she’d tried again, this time to a shoe salesman. None of it quieted the drumbeat in her chest: Hollywood.

Los Angeles gave her a new life—and a new name. A casting agent tossed out, “Tempest Storm.” The alternative was “Sunny Day.” She chose the lightning. While cocktail waitressing, a customer asked if she did striptease. She didn’t even know what that was. A few months later, she did—and discovered she could turn a room into a held breath.

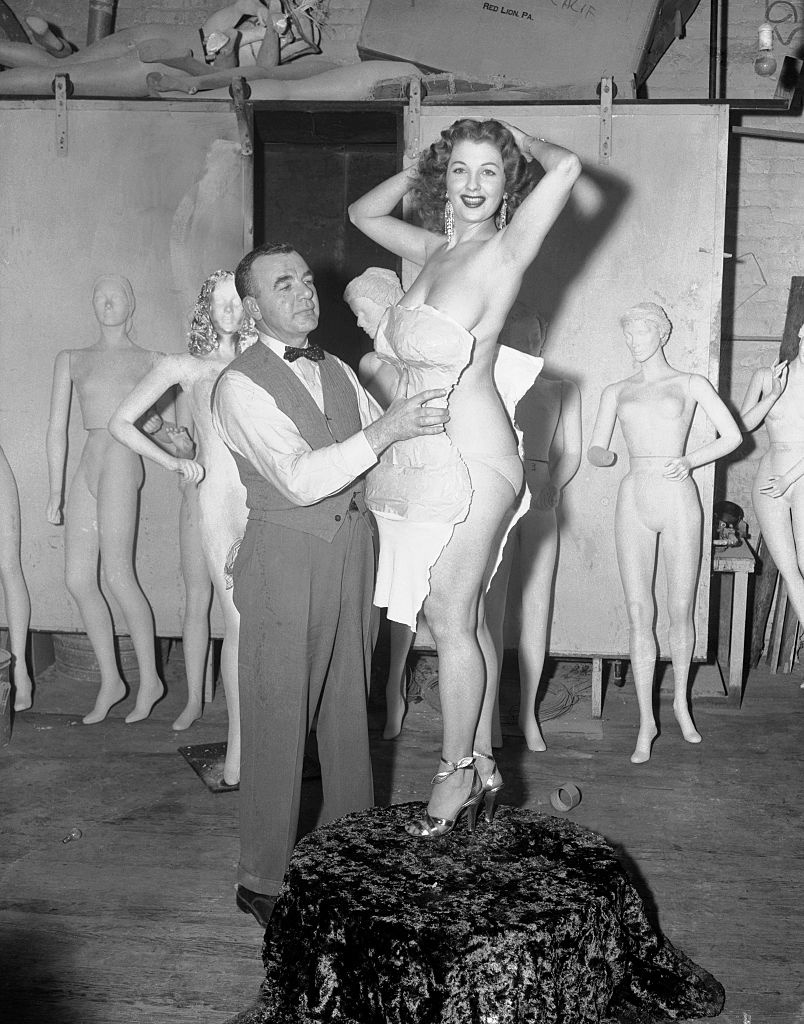

By the late 1940s she was onstage; by the mid-1950s she was a headliner. Tempest didn’t bump and grind so much as glide and tease: rhinestones, gowns, choreography, and control. Clubs advertised her like royalty; newspapers swooned; Lloyd’s of London supposedly insured her curves for a million dollars. She earned around $100,000 a year—close to a million in today’s money—and picked up nicknames like “Tempest in a D-Cup” from a press that couldn’t look away. She shared marquees with Blaze Starr and Lili St. Cyr, and winked at the censors in burlesque films like Teaserama (1955) and Buxom Beautease (1956) alongside Bettie Page.

Offstage she was disciplined in ways that surprised people: no cigarettes, no booze stronger than 7-Up, mornings of granola, afternoons of massage and sauna. She refused plastic surgery, insisting what nature gave her was enough. The public appetite could verge on chaos—at the University of Colorado in 1955, 1,500 students surged toward her like a tide.

Her personal life crackled, too. Lovers’ columns linked her with Elvis Presley, Mickey Rooney, and mobster Mickey Cohen. In 1959 she married jazz star Herb Jeffries, Hollywood’s first Black singing cowboy. They had a daughter, Patricia Ann, and broke racial taboos so thoroughly it cost Tempest work in parts of America where their marriage was still illegal. The marriage ended, but the affection didn’t.

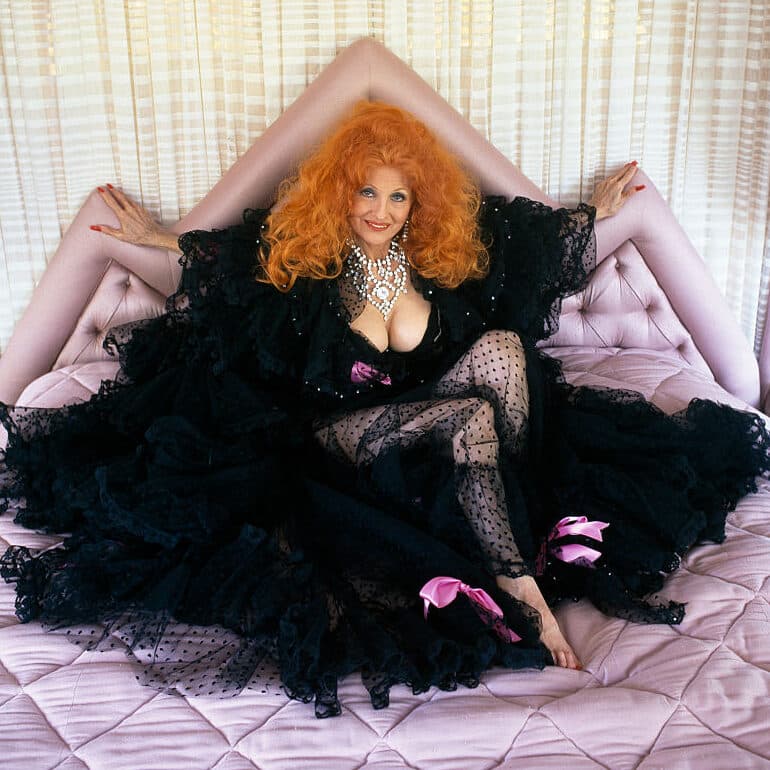

Most stars dim with time. Tempest refused. She kept performing into her sixties and even returned to the stage in her eighties, still most alive under hot lights and velvet curtains. San Francisco declared a “Tempest Storm Day” when she headlined the O’Farrell Theatre’s 30th anniversary in 1999; she was a beloved presence at Burlesque Hall of Fame events well into the 2000s. A 2016 documentary, Tempest Storm, framed the woman behind the legend.

She spent her later years in Las Vegas and died in 2021 at ninety-three, leaving more than feathers and glitter in her wake. She proved sensuality doesn’t expire, that agency can live inside a wink, and that glamour can be a kind of armor. Modern stars like Dita Von Teese name her as inspiration for a reason: Tempest Storm didn’t just ride a cultural wave; she changed its direction. Unstoppable. Unforgettable. A force of nature—right to the final bow.